Twenty-five years after the release of Push, the agonising book exploring incest, rape and HIV/AIDS, its author, Sapphire reflects on how little has changed around structural inequalities around race.

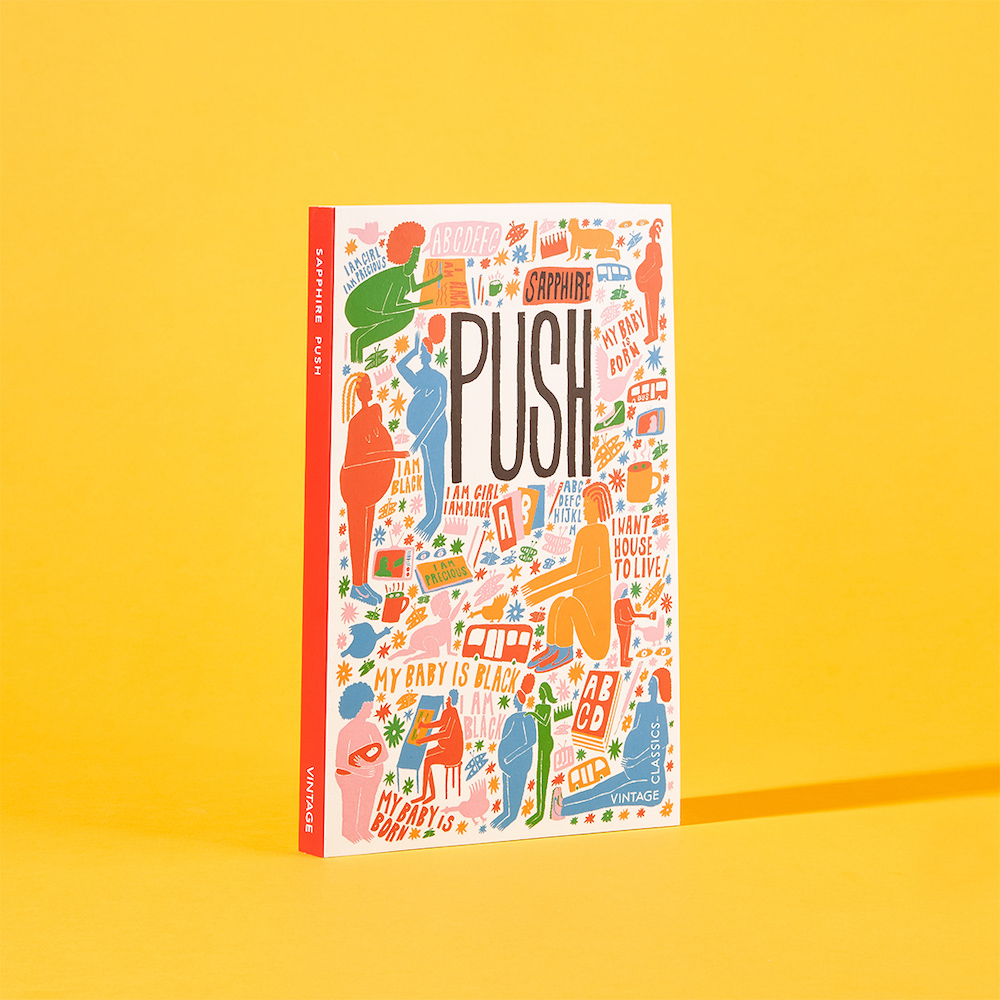

Push is the harrowing yet uplifting story of Precious Jones: sixteen years old, illiterate, pregnant by her own father for the second time and kicked out of school. Placed in an alternative teaching programme, Precious learns to read and write, finding empowerment and community among the young women in her class.

Push was first published in 1998 by American writer Sapphire, who was simultaneously praised and courted controversy for her book’s graphic account of an illiterate inner-city teenager growing up in a cycle of abuse, violence and a welfare system designed to keep her in poverty.

In the book’s new edition, released on 24 June, Sapphire discusses stark parallels between the institutional racism and classism that trapped her protagonist into a cycle of academic underperformance and dependence on welfare and how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected Black people.

Twelve years after the book was turned into an academy award winning film called Precious, starring Gabourey Sidibe, Mo’Nique and Mariah Carey, Sapphire says that like the HIV/AIDS crisis of the 80s and 90s:

“The same challenges of race and caste which beset us 25 years ago beset us now when things should be so much better. And like 25 years ago, the people dying now and being dumped in unmarked, or mass graves were employed in professions like mine and looked like me and the people I taught. COVID-19, like all diseases, hits hardest the poor, people of colour, and the socially vulnerable—people who are incarcerated, who live communally, people living in nursing homes.”

Herself the victim of childhood sexual abuse by her father at the age of eight, Sapphire is both bemused and further emboldened by the backlash against the detailed and graphic nature of her character Claireece “Precious” Jones’ rape and how much the character’s mother both enabled and blamed Precious for the abuse.

“We screened Precious to 99% white Christian Mormon conservatives in Salt Lake City and we got a standing ovation. A woman of 90 stood up and said: ‘I am Precious.’” She told The Guardian in 2011.

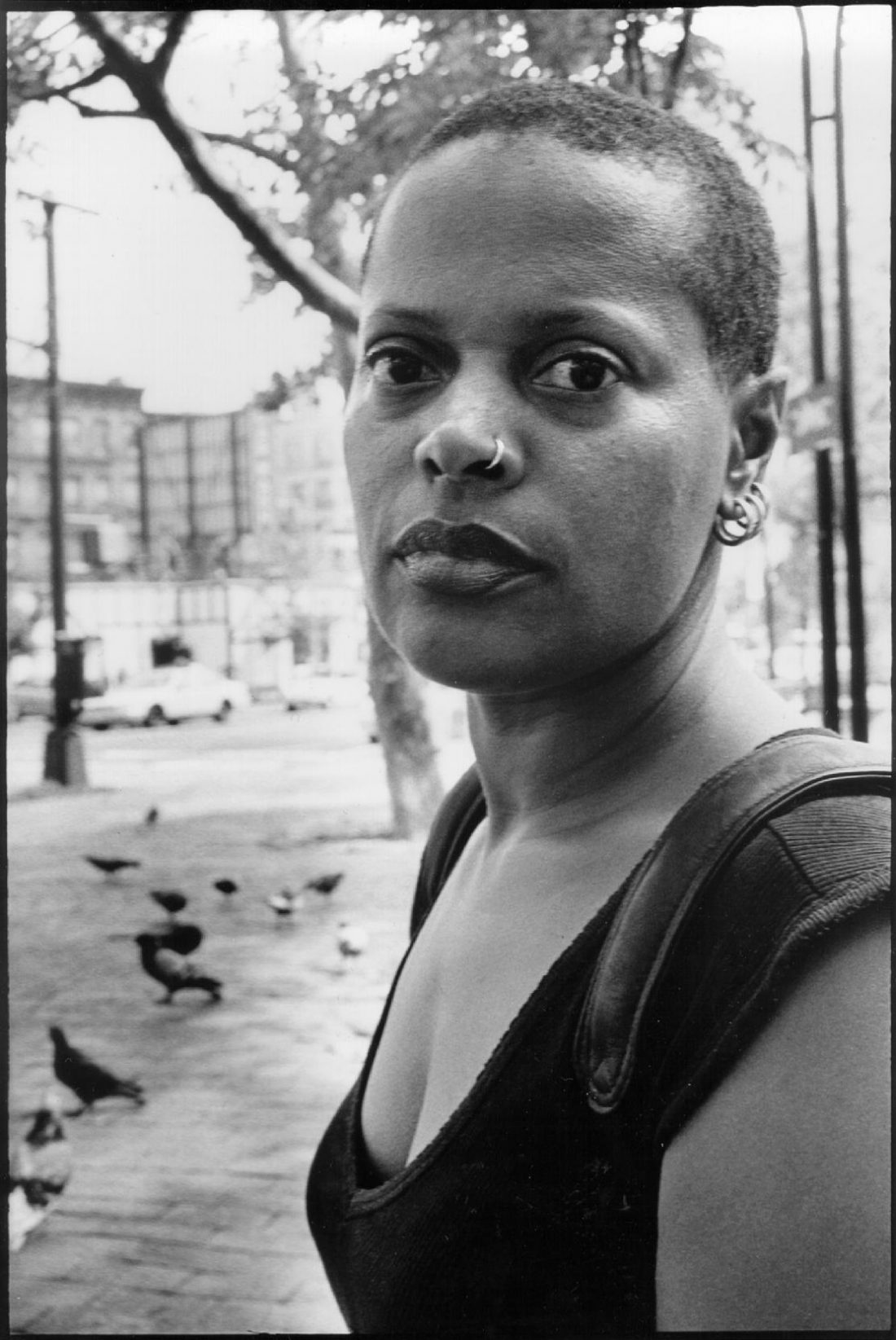

Image credit: Lina Pallotta

In the new edition of the book’s afterword, Sapphire reiterates: “The stories in Push of girls like Precious are not unusual. It was in Bronx Community College that a student in my ABE (Adult Basic Education) class at first confused me. I knew she was 33-years old [and] one day she mentioned that she had to pick up her daughter and that that daughter was twenty years old. The numbers were jarring. If she had a 21-old daughter… Evidently knowing what I was thinking, she said: “I had a baby by my father when I was 13-years old, and she has Downs Syndrome.”

Sapphire admits that part of the reason she decided to continue the story was because of the encouragement and interest that Push received in scholarly conversations. Sapphire’s work is also included in the 2019 anthology New Daughters of Africa, edited by Margaret Busby.

The new edition of Push featuring an introduction by Tayari Jones is available on 24 June and is published by Vintage Classics in paperback and ebook.

Buy the book here.

This article was written by Katrina Marshall.