In our exclusive interview with Dame Elizabeth Anionwu, the iconic Professor of Nursing talks about her journey to accepting her mixed heritage and describes her work in Sickle Cell treatment as her life’s greatest achievement.

“I washed my face up to ten times at one point to become white…”

Delivered with blithe matter-of-factness and not a shred of self-pity, this was the sentence that stopped me in my tracks when I sat to interview Emeritus Professor of Nursing at the University of West London, Dame Elizabeth Anionwu.

Image credit: David Gee

Hers is a story of how literature and tenacity; a questioning nature and finally acceptance, formed a clear picture of precisely who she is, at a time when being of white Irish and Black Nigerian (mixed) heritage could bring more pain than pleasure. Yet there is no trace of that confused little girl, in the woman with the kind and expressive eyes and skin the colour of caramel speaking to me on a Zoom call this hazy afternoon in the middle of the week.

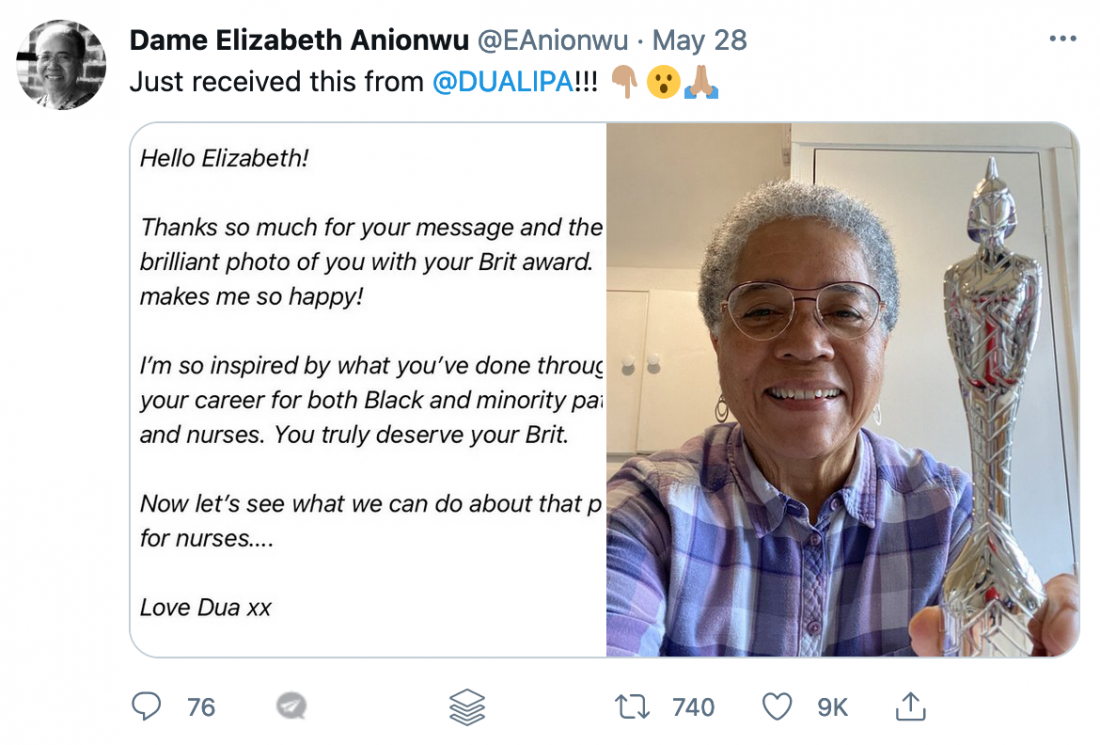

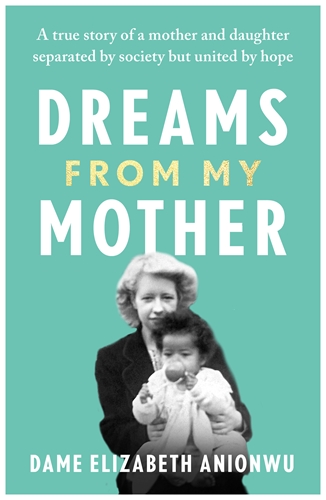

I spoke with Dame Elizabeth as she prepares to launch her book Dreams From my Mother in September this year. Through excitement over the pop stars she has rubbed shoulders with [Dua Lipa named Dame Elizabeth as her personal best British female of the year at this year’s Brit Awards] to her career as a compassionate nurse and how the writings of Franz Fanon began a life in which both her passion for nursing and her self-assurance is rooted.

As much as I remain in awe of her pioneering work as the UK’s first nursing specialist for Sickle Cell Disease and Thalassemia, her widest smile came from recalling her achievements as a mother and grandmother.

An endearing picture of where her priorities lie, for a woman who has shaken hands with more members of the British Royal Family than most of us could ever dream of. To say nothing of the encyclopaedic list of acronyms and professional awards that trail languidly behind her name whenever it appears in print.

With sharp candour, tempered by genuine humility, she recalls the origins of her passion for nursing as a master class in human compassion as a child in a children’s home of the Nazareth House Convents in the mid 1950s. Needing regular treatment for severe childhood eczema, one of the nuns used distraction therapy to keep the nine-year old Elizabeth giggling while removing her bandages. Other nuns would tear the bandages off as it stuck to her skin, causing it to painfully tear and bleed. This nun was different.

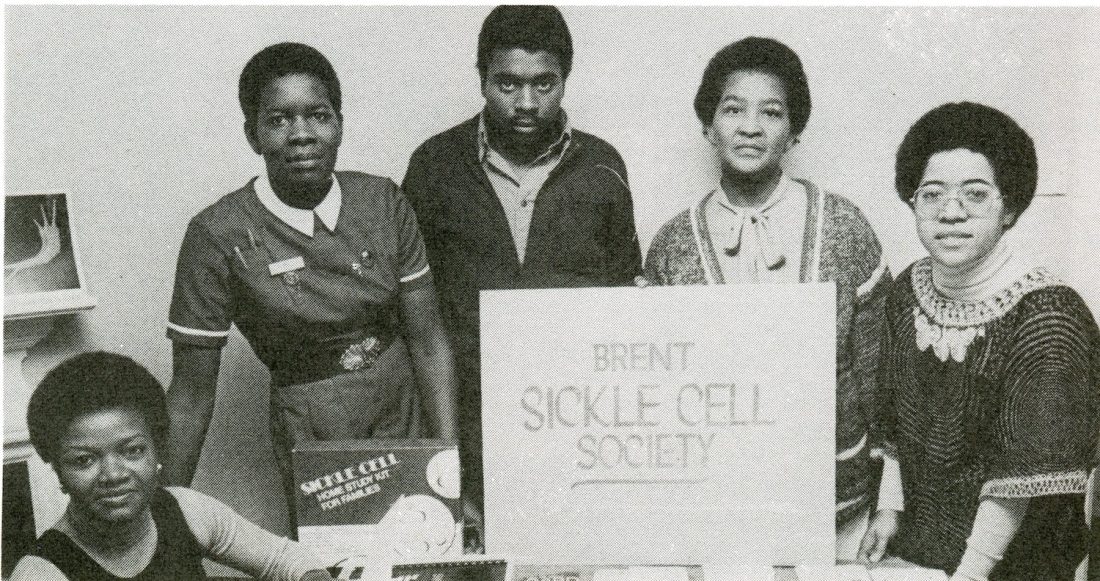

Dame Elizabeth Anionwu – 2nd from right, back row.

“She wore a white habit rather than the traditional black habit and later on before I left the convent, I learnt that she was a nun, but she was also a nurse. And that’s when I decided I wanted to be a nurse because I associated this woman with laughter, not having any pain. And caring.” Dame Elizabeth explained, smiling.

With that decision firmly cemented in her future plans, it was yet another act of kindness, this time from a French African midwife, that set Elizabeth – then living in Paris in the late 1960s – on another journey through Black activism and self-discovery through her relationship with the written word.

*Shortly before this interview I reviewed the highly emotive BBC documentary Subnormal – about the mis-categorisation of Black West Indian students as educationally sub normal and placed in special UK schools in the 1960s.

The research was eventually turned into a book that led to the upgraded Education Act of 1981 which removed the word from use in the sector. In a delightful spot of synchronicity, this book was published by the same Black publisher who gave Elizabeth access to the books that she believes ignited her eventual reconciliation with being of mixed heritage.

“She’d heard my story of washing my face ten times and she said Elizabeth, the book you need to read is Franz fanon’s Black Skin White Mask and that was the book that… just… the scales just fell off my eyes. You see I didn’t who my father was. I had my mother’s Irish surname. That was my first contact with people from diverse backgrounds. Mainly African Black Caribbean. And so, I just thought I need to find out who the heck I am! Because Fanon had really set out for me the damage that was being done to me. It was so clear that we – Brown skinned, Black skinned individuals – when we were in an environment where the people in power with authority were white and saw us in a negative light; we subsumed that gradually so that we didn’t like ourselves. And that was the big lightbulb moment for me.” She explained excitedly.

I suddenly found my father Lawrence Odiatu Victor Anionwu (known affectionately as LOV) when I was 25. Changed my surname to his 4 years later. Seen here with him in his hometown of #Onitsha #Nigeria Was to know him for only 8 years before his sudden death #OTD 12th June 1980. pic.twitter.com/PT2766osCu

— Dame Elizabeth Anionwu (@EAnionwu) June 12, 2018

Sure enough, upon her return to London, Dame Elizabeth threw herself into Black community activities that included the Black publication movement. She befriended and volunteered for Jessica and Eric Huntley, founders of Bogle Overture Publication – who published the controversial analysis of British education among West Indian children by Bernard Coard in 1971.

In her little Mini Cooper, the 22-year-old zipped around England with boxes of books on Black identity and race theory and set them up in the back of community halls where lectures and public speeches were taking place. At the same time, she had managed to qualify as a health visitor in the same year and practiced for three years in Brent.

It was the sweet spot between working with the community and being generally concerned with the peculiar needs of Black families that inevitably led Dame Elizabeth into specializing in Sickle Cell treatment.

By now it probably seems strange to make only passing mentions of Dame Elizabeth’s stellar career – work she doesn’t appear keen on stopping any time soon. Indeed, despite a CBE and Damehood in recognition of her services to nursing and health equality, the woman who boldly took on her father’s Nigerian name after a long and serendipitous quest to locate him, cites pride in her daughter and granddaughter’s achievements as the proudest moments in her life.

In that spirit it is important to highlight how much self-awareness and the intersection of race and healthcare is both personal and professional for the woman who is listed as one of the 70 most influential individuals in the 70+ year history of the National Health Service (NHS).

However, these achievements were hard won – both because of her race and her gender.

With her tell-tale dry delivery of memories that are less than pleasant, her challenge of the way data was being collected from citizens from what was then called the “new Commonwealth” [i.e., Black and Brown people] once cost her a pass mark in her examination to become a full-fledged health visitor. This research was to support grant funding for services like interpreters for newly arrived Gujurati speaking south Asian refugees from Uganda and Kenya.

“We were visiting some of these families. The health visitors were doing sign language with them, particularly the elders. And I’m thinking if they are getting money for this group of people why haven’t they got any interpreters? Well, that was a step too far for the health visitor supervisor and she failed me. She failed me on the practical section of my course. I was doing very well on the practical side until I dared to question. Failing as a health visitor student meant I could never become a health visitor.”

At this point her connections with grassroots political activism came in handy. Encouragement from a small health services activist group called NEEDLE of which she was a member, led to her putting in a call to the manager of the service to report the matter. Needless to say, the failing grade was overturned and the rest of her groundbreaking work with Sickle Cell and Thalassemia is living history.

Dame Elizabeth Anionwu – far right of photo

There is never enough space in print to do justice to a life as rich and authentically lived in service to others as that of Dame Elizabeth Anionwu. As the afternoon shadows grew longer, I knew it was time to wrap up, though I felt like I’d met an aunty I’d known in a former life and we were just getting reacquainted.

I asked for her projections for the practice of nursing in the next 20 years – having presided over the evolution of the profession for most of her life. With a rare furrowing of her brow, she lamented the disparity in funding for Sickle Cell and Thalassemia research vs. that of certain cancers and diseases like cystic fibrosis. Sickle Cell admission in London Hospitals features in the top 16% of all Accident and Emergency admissions.

“[However], The problem at the moment is that a student nurse can leave a three-year programme and not have received any information about Sickle Cell in their whole three years. It is very ad hoc. Unless you get colleges of nursing and NHS trusts embedding education about Sickle Cell within their routine courses, you will have these dreadful situations where if you go around the country, you’ll find nurses with one or two years’ experience having no training in Sickle Cell at all from the clinical side, let alone the peripheral considerations of the disease. And I think it is just scandalous.”

It’s clear that the situation is extremely complex. Dame Elizabeth ponders if in 20 years’ time we will still be having to fight for Black and minority ethnic nurses to attain the career progression they are eminently qualified to have and wish to have. She’s saddened by the hurdles of that reality ever coming to fruition. But with the foundation she has laid at the intersection of health and race equality, she has certainly done more than her bit toward the realisation of this outcome.

Dreams From My Mother will be released in September 2021 and is already available for pre-order.

This article was written by Katrina Marshall.