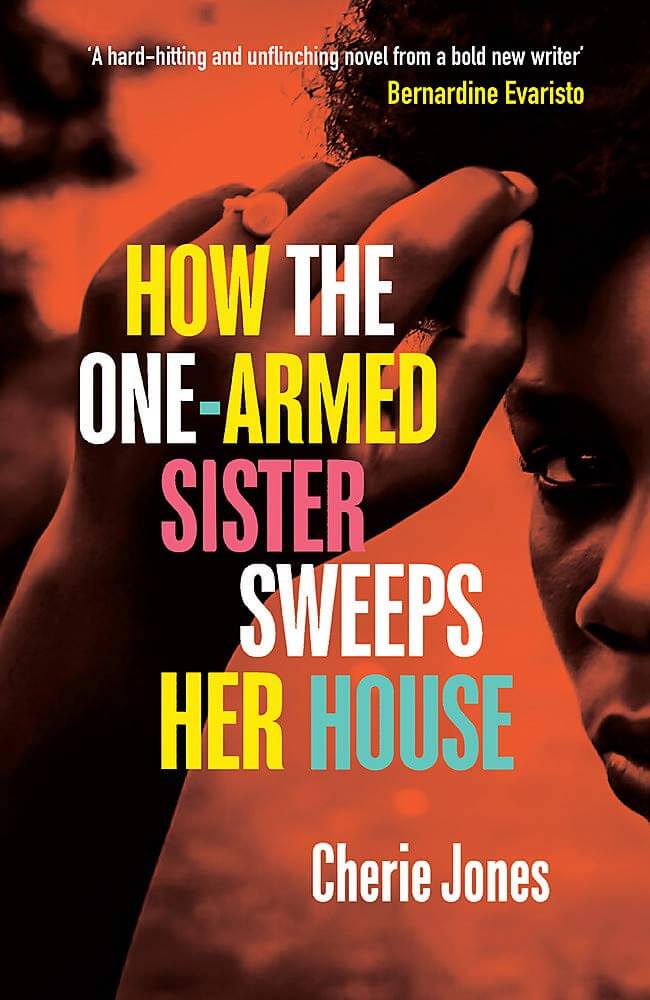

How The One-Armed Sister Sweeps Her House is Cherie Jones’ compelling debut novel about a troubled island, of male violence and the women who live with it and fight to survive.

Set in Barbados, Jones’s debut novel follows four people each desperate to escape their legacy of violence in a so-called “paradise.”

In Baxter Beach, Barbados, moneyed ex-pats clash with the locals who often end up serving them: braiding their hair, minding their children, and selling them drugs. Lala lives on the beach with her husband, Adan, a petty criminal with endless charisma whose thwarted burglary of one of the Baxter Beach mansions sets off a chain of events with terrible consequences.

Acclaimed author Diana Evans said: “Cherie Jones has talent abounding, drawing us with skill, delicacy and glorious style into a vortex of Bajan lives on the edge, clashing across class and colour divides. This is one of the strongest, most assured and heart-wrenching debuts I have ever read.”

Readers of My Sister The Serial Killer and An American Marriage will love this debut novel from Cherie Jones.

Here, Melan Magazine readers can enjoy an extract of the book.

Warning: Contains graphic description of traumatic birth delivery.

“… And right when she comes back outside to ask a nurse or a guard or another one of the sick and waiting whether they have a pack of tissues or baby wipes or a napkin from a forgotten sandwich, a voice calls her name over the PA system and the grey doors open and a nurse appears, a squat woman with an ill-fitting wig and a uniform too white to suggest a good bedside manner and the nurse says hurry up we don’t have all night and Lala does not move because now she’s wet herself and she’s embarrassed and hurting worse than before and the nurse sucks her teeth because now it will have to be cleaned up and didn’t she know she wanted to go and then she notices Lala’s belly is rounder than just fat and she notices the bloody prints the soles of Adan’s sneakers have made on the green-grey floor and she shouts. A stretcher comes, and Lala is lying down when she enters the doors, and she passes into a hallway with prone people groaning. She sees arms held at odd angles and gashes and wounds and shirts and towels being pressed to foreheads and mouths and bleeding places and she looks up to spare herself and there is a grid of roof-tiles and square fluorescent lights tic-tac-toeing into the future and Lala wonders whether, after all she has already been through, she is going to die here. And the thought does not distress her. The stretcher stops and another nurse appears and when next she comes to, they are telling her to push but Lala does not want to push because she is afraid of what she will find.

Lala learns the second thing, because when she opens her mouth to ask for water the scream she has been hiding comes out instead. Lala wants to tell them, this is not my scream, this is a scream I picked up from a house on Baxter’s Beach, because she is hoping that the nurses will understand that this scream will also require treatment, but they don’t. The nurse with the bad Boney M wig says shut up and asks her if this is how she was screaming when she was taking the man that got her into this mess. Her eyes tell Lala that she cannot, will not, allow Lala’s screaming to get into her own head because it doesn’t look good and these teenaged girls without a pot to piss in are in here every day at younger and younger ages.

So, Lala closes her mouth and swallows the scream she caught on Baxter’s Beach the way some people catch a cold and in her mind she begs the baby not to die as she pushes and feels the vessels in the whites of her eyes pop and flood her vision.

And Lala learns the third thing, because when she gets past the stinging, and the tearing and the stretching and the slippage and is suddenly, breathlessly freed of a weight she has been carrying within her for the past eight months, she recognizes that she does not hear the squall that, in every television depiction she has ever watched, signals the birth of the baby. So she says ‘Nurse, nurse?’ because she wants the reassurance that everything is alright, that the baby is fine, but the nurse does not look at her, the nurse wrenches her wrist out of Lala’s grasp and tells the other nurse to call the doctor and her hands are holding something that does not move. She is rushing the baby to the spot of light under a lit lamp on a table, putting a bulbous tube into its nostrils, rubbing and pressing and listening to the baby’s chest. And Lala understands that it is not good and she does not want to look but she does and she wills the baby to live because she can see that the nurses have already given up and because, suddenly, she is angry that Adan is not there and after tonight, she is sure that she can no longer love Adan and perhaps the baby is all the good in him and she wants it to live so she can love it instead. Another nurse bursts into the room and a very young student doctor is behind her and it is the two of them who stand over her baby on the small side table and slap it and prod it and prick it with tubes and needles until Lala hears a weak little cry. And it is only after Lala starts to whimper her relief that the student says, ‘Is she stitched up?’ and the nurse who worked on saving Baby says ‘No’ and comes back to her and pats her arm and says it is ok, they are doing everything they can.

By the time they are done Baby is still blue, but she is breathing, and she is taken from the small, white table and shown briefly to her mother and then whisked away and the room is quiet while Lala is stitched up and stabbed with more needles and transfused with someone else’s blood and she is cold and she is shaking and the nurse with the wig is wrapping Wilma’s blood-soaked nightie in a ball and putting it into a bag and preparing the room for another delivery and Lala asks if they can call Wilma and tell her Stella had the baby and ask her to come, even though she knows that Wilma will not come. And the nurse, unimpressed by the fact that Lala calls her grandmother by her first name, but softened by Lala’s apparent ability to beat the odds, says Ok but the baby probably won’t be able to have visitors for a while. And her tone says maybe the baby will never see visitors. And she leaves Lala in the cold quiet room on her back with her legs still splayed and no feeling at all at the intersection of her thighs and it is nothing like the bliss on the posters in the clinic or on the TV ads or the faces of the wealthy tourist women who walk with their newborns on Baxter’s Beach. Instead, she realises that she has now brought another person into the dark, that birth is an injury and having the baby has scarred her and when the nurse asks her if she wants to go with her to see her baby in ICU she shakes no and the nurse clucks tsk tsk and Lala thinks of Adan, who hasn’t come back and she wonders if he went back for the gun but she keeps her mouth closed because some of the scream is still in there.”

How The One-Armed Sister Sweeps Her House published in hardback (£12.99), ebook and audio on 21 January 2021.

Buy the book here.