Every year, 19 June marks World Sickle Cell Awareness Day, an opportunity to place the sickle cell disease front of mind and to bring greater understanding of the symptoms and difficulties facing millions of people who suffer with the disease worldwide.

Quite worryingly, in spite of its reputation of being a disease that affects predominantly people of colour, many of us still don’t know much about the disease, working under assumptions of half-truths and hearsay. The sickle cell disease refers to a group of inherited conditions that affect the red blood cells. It mainly affects people of African and Caribbean descent in the UK, but is also present in Asian, Arab and Mediterranean people.

The most common form is Sickle Cell Anaemia, where sufferers have the sickle (crescent-shaped) haemoglobin (HbS). This means that the red blood cells are devoid of oxygen and are unable to move around like normal blood cells (Hba), which are donut shaped. Because the cells are unable to move, they stick together, blocking blood vessels which causes tissue and organ damage, as well as severe bouts of pain known as a ‘Sickle Cell Crisis’ or a ‘Vaso-Occlusive Crisis.’

The most common form is Sickle Cell Anaemia, where sufferers have the sickle (crescent-shaped) haemoglobin (HbS). This means that the red blood cells are devoid of oxygen and are unable to move around like normal blood cells (Hba), which are donut shaped. Because the cells are unable to move, they stick together, blocking blood vessels which causes tissue and organ damage, as well as severe bouts of pain known as a ‘Sickle Cell Crisis’ or a ‘Vaso-Occlusive Crisis.’

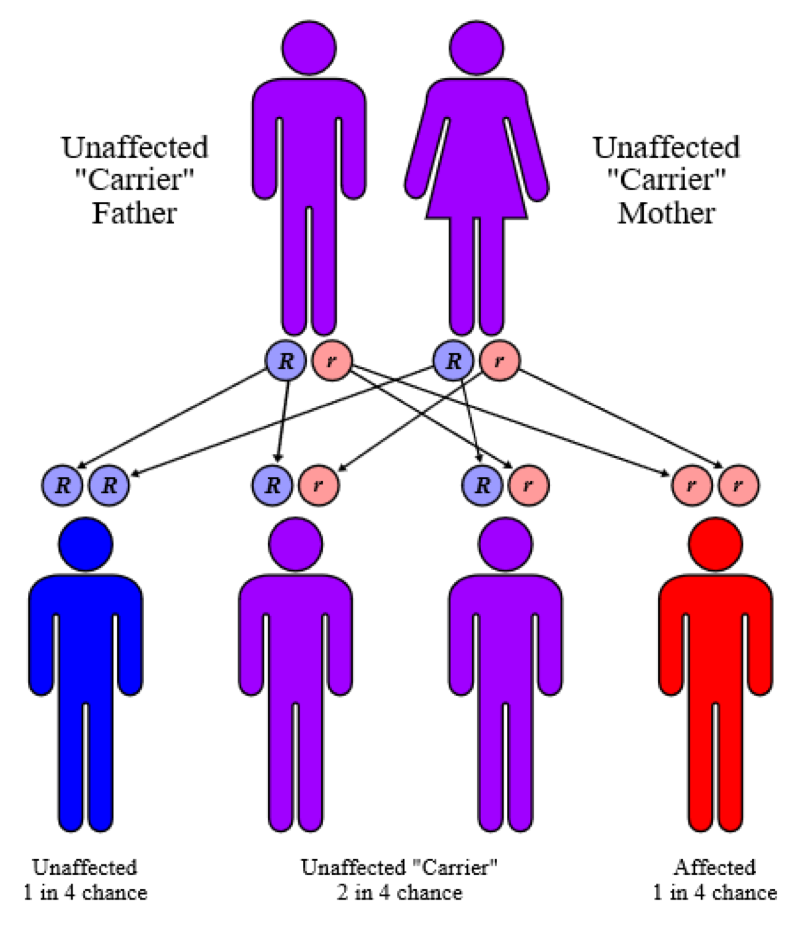

A common grey area in people’s understanding is how you ‘get’ sickle cell disease. You will have sickle cell when you inherit the ‘defective’ gene from both of your parents. If you only inherit the gene from one parent then you will have the sickle cell trait. It is likely that your blood will contain some sickle cells, but you will still be able to produce normal haemoglobin, and you won’t usually experience any symptoms.

Image: A chart showing how sickle cell is passed on

Earlier this year in March 2017, it was reported that scientists had managed to reverse a French teenager’s sickle cell, using pioneering treatment to change his DNA. The teenager who’d previously had very severe symptoms as a result of the disease, is now producing red blood cells normally, essentially, ‘getting his life back’! The world-first procedure at Necker Children’s Hospital in Paris will no doubt offer a beacon of hope that a cure for the disease is one step closer.

Ade’s experience

As a child, Ade Hastrup found it tough living with sickle cell. From a very young age she knew that she was different. She couldn’t do things other children could do. Ade recalls wanting to join her sister in a marathon, but their mum didn’t want her to. She ran the marathon anyway, but at a cost:

“I didn’t understand what my triggers were, and I kept pushing and pushing myself to a point where my oxygen levels dropped and my blood began to sickle.”

Since then, Ade has tried to maintain her oxygen levels, but a crisis can be triggered by different factors such as stress, dehydration, infection, and unexpected weather changes. The degree of the crisis also varies, and sometimes Ade self-medicates, which she is allowed to do.

“If the level of pain is a 6 then I know I have to start the medication process – the tablets I use group in grades, and sometimes those would be good enough, but sometimes it isn’t, so I would have to use stronger ones. And if that hasn’t worked then I have to go to hospital.”

Ade’s type of sickle cell comes with a 1 in 200 chance of a crisis occurring in the hip. This happened to her which lead to a hip replacement.

“I have an artificial hip. About 10 years ago I had a total hip replacement, so you can imagine what it’s like when I go through airports (laughs).”

The crisis ended up killing the head of my femur bone. Over the years, the bone would wear and tear. It got to a point where one leg was shorter than the other. I lost two inches of my spine and it started to curve. Getting out of the car was a nightmare – I’d have to jerk my hip back into place because it didn’t have a head anymore.”

Ade’s sickle cell, also means she has a 1 in 200 chance of sudden blindness, so every year, she has her retinas checked.

As a teacher and deputy head, Ade has a coping mechanism she sticks to, to get by:

“I have to limit what I do. I do playground duties when I need to. I don’t really have to take a lot of time off. Sometimes I can work through the pain. It’s not ideal but no-one forces me to do it. It’s my choice. If I can still function through that pain then I will soldier through it.”

A sickle cell crisis can occur at any given moment. Ade describes a recent incident.

“I had just finished teaching and managed to make it back to my office. I wanted to go home and self-medicate but my work colleagues were worried about me driving. So, I had to wait for an ambulance.”

Despite the reality of having a crisis at work, Ade is still determined to be the best that she can be, and to show others with sickle cell that they can achieve their goals.

“People with sickle cell can live a fulfilled live – I’m proof of that. Against the odds, as Maya Angelou said: “still, I rise.”

For Bunmi Otuyemi, living with sickle cell is easier when you have a goal to occupy yourself with. She has been a solicitor for 20 years, Running her own firm. Before becoming a solicitor, Bunmi was a qualified teacher in Nigeria, where she was born. She came to the UK to teach but decided to pursue a career in law instead.

“Studying law at university was the most stressful time for me. There were times when I couldn’t concentrate because of the pain. I couldn’t go to parties with my friends in case I fell ill, but I was determined to get through it and finish.”

Bunmi doesn’t have as many ‘bad days’ as she used to, but she has had several crises at work. “I’ve had an ambulance called for me three or four times in the last few years.”

Bunmi, like Ade was the only one out of her four siblings who inherited the blood disorder, but she was not the first to be born with the condition.

“I had an older sister who died of sickle cell before I was born.”

Growing up in Nigeria, Bunmi faced many challenges during her childhood. She was only able to complete a few weeks of boarding school. While she was there, she couldn’t take part in P.E lessons. Instead she would sit in the corner and watch the other children run around. When she was 16, she had a serious crisis with her legs.

“I was in bed for three years; my joints were swollen and I couldn’t walk. It’s common in parts of west Africa for people to die from sickle cell when they are between 15 to 20 years old. Everyone feared for my life, so when I got to 18, 20+ – they were all surprised, but thankful.”

As well as being a full-time solicitor, Bunmi also runs a charity called Sickle Cell Scheme which raises money for young people in Nigeria and Ghana who want to study.

“The mentality for many parents in Nigeria and Ghana is that if your child has sickle cell, they will die soon, so there is a reluctance to pay the fees that will send them to school.”

“We should never give up. I have two friends with sickle cell, one is a barrister and the other is a doctor. We shouldn’t let the fear of death stop us because it is fear that kills us in the end.”

1 comment